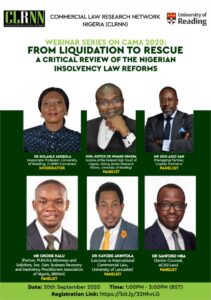

The Commercial Law Research Network Nigeria (CLRNN), webinar on insolvency law reform in Nigeria was held on 30th September 2020, the eve of the celebration of Nigeria’s 60th anniversary as an independent nation. September also marked the celebration of 12 months of CLRNN, a network established to promote research and knowledge exchange on matters relating to the development and reform of commercial law in Nigeria. CLRNN has at its heart, a desire for collaborative consultation amongst several stakeholder groups who research, practice, adjudicate and regulate the commercial law sphere in Nigeria. Panellists for the webinar were pulled from academia, practice and the judiciary and they included Mr Seni Adio SAN, whose presided over the 2020 reforms as President of the Nigerian Bar Associations’ Section on Business Law (NBA-SBL), Mr Okorie Kalu, Secretary General of the Business Recovery and Insolvency Practitioners’ Association of Nigeria (BRIPAN), Hon Justice Dr Nnamdi Dimgba, a Judge of the Federal High Court of Nigeria, Dr Kayode Akintola, academic and insolvency expert, and Dr Sanford Mba, practitioner and insolvency expert. The Panel was chaired by Dr Bolanle Adebola, academic, insolvency expert and convener, CLRNN.

The Commercial Law Research Network Nigeria (CLRNN), webinar on insolvency law reform in Nigeria was held on 30th September 2020, the eve of the celebration of Nigeria’s 60th anniversary as an independent nation. September also marked the celebration of 12 months of CLRNN, a network established to promote research and knowledge exchange on matters relating to the development and reform of commercial law in Nigeria. CLRNN has at its heart, a desire for collaborative consultation amongst several stakeholder groups who research, practice, adjudicate and regulate the commercial law sphere in Nigeria. Panellists for the webinar were pulled from academia, practice and the judiciary and they included Mr Seni Adio SAN, whose presided over the 2020 reforms as President of the Nigerian Bar Associations’ Section on Business Law (NBA-SBL), Mr Okorie Kalu, Secretary General of the Business Recovery and Insolvency Practitioners’ Association of Nigeria (BRIPAN), Hon Justice Dr Nnamdi Dimgba, a Judge of the Federal High Court of Nigeria, Dr Kayode Akintola, academic and insolvency expert, and Dr Sanford Mba, practitioner and insolvency expert. The Panel was chaired by Dr Bolanle Adebola, academic, insolvency expert and convener, CLRNN.

The insolvency law of Nigeria can be found within the Companies and Allied Matters Act 2020, which reformed and repealed CAMA 1990, an act described by Prof Emmanuel Akanki, one of Nigeria’s leading company law scholars, as a landmark company legislation because it was the first indigenous company law in Nigeria. He stated:

‘Historically, those responsible for the formulation of the 1990 Companies and Allied Matters Act would be cited and remembered as the makers of our tradition in progressive Company Law reform and development. We have not seen it before in this country – law reform based on assiduous and painstaking research combined with enquiries spanning English-speaking jurisdictions.’

E.O.Akanki, ‘Company Law Development Through the 1990 Legislation’ in A.O Obilade, A Blueprint for Nigerian Law: A collection of critical essays written in commemoration of the thirteenth anniversary of the establishment of the Faculty of Law of the University of Lagos (Faculty of Law, University of Lagos, 1995), Chapter 5.

To understand the structure and spirit of Nigeria’s company law, it is imperative to explore the history of Nigeria and origins of its laws. Given that Black History Month is celebrated in October in the United Kingdom, the webinar also contributed an event highlighting colonialism and its continued implications for African countries today.

CAMA 1990 was born out of the need to create a comprehensive body of legal principles and rules suitable to the Nigerian situation.

Prior to CAMA 1990, Nigeria had regulated its corporate space by indigenising British Company Law. Our first indigenised Corporate Law was the Companies Ordinance 1912 that simply transplanted the British Companies (Consolidation) Act 1908 into the Nigerian space. With the amalgamation of Southern and Northern Nigeria in 1914, the Companies Amendment and Extension Act 1917 was enacted to extend company law to the entire country. Five years later, both the Ordinance of 1912 and that of 1917 were repealed and replaced by the Companies Ordinance 1922, which was modeled on the British Companies Act 1929. The 1922 Ordinance was amended by subsequent ordinances in the following decades based on subsequently enacted British Companies Acts. The last indigenised Companies’ Act was the British Companies Act 1948 which was introduced into Nigeria through the Companies Decree 1968. Incidentally, at the time the 1968 Decree was promulgated, the British Companies Act 1948 had been amended by the Companies Act 1967 but no attention was paid to that in Nigeria. As the failure of the 1968 Decree to support economic development in Nigeria during the (post) oil-boom era became more apparent, there were heightened calls for its amendment or repeal.

Prof Olakunle Orojo, another leading company law scholar, noted:

‘One of the major criticisms of the Act is that it is little more than the putting together of some of the sections of the repealed companies Act, Cap. 37 and some sections of the English Companies Act, 1948 instead of taking the bold step of codifying both the statutory and case law on companies…. The preparation of such a code would have provided the opportunity for reviewing and modifying some of the more inconvenient common law rules.’

Nigerian Company Law and Practice, (Vol. 1) cited in ‘Report on the Reform of Nigerian Company Law and Related Matters’, (Volume 1, Review and Recommendation, 1988), Introduction.

In March 1987, Prince Bola Ajibola SAN, then Attorney General of the Federation and Minister for Justice, directed the newly established, Nigerian Law Reform Commission to undertake a review of the Nigerian company law, to provide laws that were better suited to the peculiarities of the rapidly developing Nigerian corporate sector. The Commission asserted in its report that it preferred a Participatory Approach to law reform, through which it engaged with social agents of change Nigeria. The commission rejected the suggestion to directly transplant modern company law from another developing or developed jurisdiction. It explained that the transplanted laws may not suit the peculiarities of the Nigerian system because they were not designed for the Nigerian society, although they may have similar principles.. The Commission recognised, nevertheless, that Nigeria did not have fully conceived, purely indigenous company law. On that basis, it struck a pragmatic compromise through which CAMA 1990 was structurally aligned with the British style for the sake of clarity and continuity, but conceptually novel with the introduction of the Nigerian interpretation of some key concepts.

The approach of the commission is illustrated through the Nigerian twist to the British receivership concept. The Nigerian receiver/manager distinguished itself from its British roots through the introduction of s390 CAMA1990, which required the Nigerian receiver/manager with power over all the assets of the company to act in the best interest of the various stakeholder groups of the company and have due but not exclusive regard for the charge holder. This concept of receivership was distinct from that of its British progenitor whose regard was solely for the chargee (appointor). We see, therefore, that the challenges of receivership/management as conceived of and practised by the British was considered problematic in Nigeria as far back as 1988. The British lawmaker would only come to that conclusion almost two decades later in 2002/3.

In 2020, Nigeria celebrated the reform of our landmark CAMA 1990 after 30 years.

It is interesting to note that the reformers have largely ignored the 1990 era ‘tradition in progressive Company Law reform and development’ described by Prof Akanki. Instead, they have re-introduced the indigenisation practices of the pre-CAMA reform era and thus, transplanted company and insolvency law from England and Wales into the Nigerian corporate sphere. A practice derisively described as merely reactionary by the Nigerian Law Reform Commission in 1987. Moreover, unlike CAMA 1990 which came with an annotated guide and explanation, CAMA 2020 is unaided. It, therefore, is difficult to understand the reasons for the precious few changes we find. Finally, although we have transplanted the insolvency law, we have neither included the complementary insolvency rules, nor codified revisions found in case law, thereby crippling the new framework. It is also ironic that like with the 1968 corporate law reforms, Nigeria has once again ignored the latest reforms to the laws being transplanted, thereby introducing out of date law into its corporate and insolvency sphere.

Over the next weeks, three of our panellists, Justice Dimgba, Mr Kalu and Dr Mba, will provide insights into various aspects of the CAMA 2020 changes to the Nigerian insolvency framework. Justice Dimgba’s essay entitled “Changes to Nigeria’s Insolvency System by the Companies and Allied Matter Act, 2020: A Judicial Perspective” will examine the charge laid down for judges in the new law. Mr Kalu’s essay entitled “From Liquidation to Rescue – A Critical Review of the Nigerian Insolvency Law Reforms” sets out the context in which the new changes were made. Dr Mba’s essay entitled “A Critical Assessment of the Moratorium Provisions in CAMA 2020” provides a critique of some of the reforms. Early Career Researcher, Mr Victor Olusegun also provides an overview of the series from the perspective of a new entrant into this area titled “A Reflection on the CLRNN Webinar Series on CAMA 2020”.

You can view the webinar and presentations of other Panelists through our YouTube page. Please subscribe for access to subsequent videos.